In August 2014, as a demonstration was about the denial of reproductive rights to Irish women over the past 40 years, was being planned, another story broke in the media, that of a woman named initially as ‘ Migrant x” and subsequently referred to as Ms Y. The woman had arrived in Ireland as a refugee claiming Asylum. On discovering that she was pregnant, she requested a termination. Her request was not met and she went on hunger strike and was judged to be suicidal and entitled to an abortion to save her life. Instead, she ended up being obliged to undergo a Caesarian section. The video of the London demonstration, outside the Irish Embassy is here: Silenced Screams, August 2014

Souces for Irish History Month talk on Rosie Hacket & IWWU re Easter 1916

Wednesday 22nd April, Irish History Month seminar, hosted by London Metropolitan University, Irish Studies and Working Lives: The Workers Before During and after the 1916 Rising. See details at: http://met.ac/jstxq

Speakers are Marian Larragy & Geoff Bell

Marian Larragy of LIFN, will talk Irish Women Workers, including Rosie Hackett

For anyone who would like to follow up on the period, this is a short list of

Sources

Women of the Irish Revolution, Liz Gillis Mercier Press, 2014

A Nation and not a Rabble: The Irish Revolution 1913–23, Diarmaid Ferriter

Renegades – Irish Republican Women 1900-1922 (Mercier Press 2010)

Unlikely Rebels: The Gifford Girls and the Fight for Irish Freedom, Anne Clare (Mercier Press, 2011)

Dissidents – Irish Republican Women 1923-1941 (Mercier Press, 2012)

‘Unmanageable Revolutionaries’ – Women and Irish Nationalism, Margaret Ward, Pluto Press, 1983

Online info and images

‘100 Years of Women’s Struggle’ Research by: Theresa Moriarty. Published March 2008 by: SIPTU’s Equality Unit

The Countess Markievicz Memorial Lecture 2006, Kieran Mulvey, Chief Executive, Labour Relations Commission

What’s The Racket about Rosie Hackett – Campaign meeting

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZBObXK9ztRA

http://womenworkersunion.ie/?page_id=263

http://flag.blackened.net/revolt/siptu/f5_history.html

http://multitext.ucc.ie/d/James_Connolly

General background on the Lockout:

Irish Radio Podcasts on Dublin Lockout http://www.rte.ie/radio1/lockout/

https://spiritof1913.wordpress.com

http://comeheretome.com/2011/03/08/delia-larkin-and-the-jacobs-strike-committee/

Housing condition Dublin 1900: http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/exhibition/dublin/poverty_health.html

http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/exhibition/dublin/commerce/E_WomensWorkers_KE204.html

Dublin 2015 read by Speaking of IMELDA, at GPO Dublin, Easter 2015

Since no government has acted wisely

We feel forced to act the fool

The lack reproductive rights for women in Ireland

Excludes women with reproductive capacity

from full citizenship, forcing women to go abroad

While Ireland shuts its eyes

Let us rise out of this mess

Irish Men and Irish Women

And all who live in Ireland

In the name of the citizenship

Promised to us on these steps

Ninety-nine years ago

We call on the government of Ireland

To give women with reproductive capacity

their full rights as citizens

Repeal of the eight amendment

Local abortion now!

Irish Men and Irish Women

And all who live in Ireland

In the name of the citizenship

Promised to us on these steps

Ninety-nine years ago

We call on the government of Ireland

to fulfill our international obligation

To provide women with reproductive capacity

Access to their full their full reproductive rights

Repeal the eight amendment

Local abortion now!

Irish Men and Irish Women

And all who live in Ireland

In the name of the citizenship

Promised to us on these steps

Ninety-nine years ago

We call on the government of Ireland

In the name of Savita,

of Miss X, of Miss Y

and the woman in the NP case

In the name of A and B and

C and D and of all women

With reproductive capacity in this country

Repeal the eight amendment

Local abortion now!

Mairead Enright on Abortion and The Law in Ireland in the wake of the case of ‘Miss Y’

By now, most Irish women have heard the story of Miss Y; the teenage asylum-seeker pregnant as a result of rape who sought access to a life-saving abortion in Ireland, but was compelled to give birth by C-section instead. Miss Y decided to seek an abortion immediately on learning that she was pregnant. However, the pregnancy had progressed to 25 weeks by the time the baby was delivered. In the meantime, Miss Y had become extremely distressed at the prospect of continuing the pregnancy, and had made attempts on her life. The facts of the case were drip-fed into the public domain during August. Some dates and times are contested and so it is not yet possible to pinpoint the precise reasons for the delay in facilitating Miss Y’s referral for an abortion.

On August 22, the Health Service Executive published the terms of reference for an inquiry into Miss Y’s treatment. The purpose of the inquiry is to establish ‘all of the facts’ surrounding the case. However, the validity of its approach is already in question. In recent days, the draft of the inquiry’s report has been leaked to RTE, and aspects of its tentative conclusions have been discussed on television and radio. At the same time, Miss Y’s legal team have confirmed in the Irish Times that she has not yet been interviewed as part of this inquiry, and they have not seen a copy of any draft report. She may very well refuse to participate in the process when her turn comes.

The PLDPA 2013 (The law passed in the wake of Savita Halappanavar’s death in 2012) .

Miss Y was recently granted refugee status, but at the time she discovered her pregnancy she needed an exit and re-entry visa in order to travel to the UK for an abortion. Her pregnancy counsellor assisted her to apply for the visa, but it was never granted. This is not an uncommon experience for asylum-seeking women. The only route to a legal abortion in Ireland is via the procedures set out in the Protection of Life During Pregnancy Act 2013. Many people think that the Act was introduced to respond to the death of Savita Halappanavar. This is not the case. The Act responds to the 2010 decision of the European Court of Human Rights in A, B and C v. Ireland, in which the Strasbourg Court found that Ireland was obliged to set out clear procedures by which women entitled to access an abortion in Ireland could actually do so. The Act enshrines a narrow version of the 1992 Supreme Court judgment in the X case. Thus, it provides that a woman may legally access an abortion in Ireland where a panel of doctors, acting as part of a multidisciplinary team, certifies that two criteria are fulfilled: (i) there is a real and substantial risk of loss of loss of the woman’s life and (ii) that risk can only be avoided by ending the pregnancy. Other women have been granted terminations under the Act, but Miss Y’s is the first to receive publicity. There is a great deal wrong with the Act, but Miss Y’s case illustrates a number of its most important flaws.

First, the care pathways which lead a woman to apply for certification under the Act are not clear. A woman should be referred in to the certification process by her GP. But if she does not have access to a GP – or indeed, a GP she can trust – it may be some time before she can make herself heard. Women from marginalised backgrounds, teenagers and women who speak poor English are especially vulnerable in this regard.

Second, the Act does nothing to flesh out the very broad ‘X case’ test for access to abortion. At the time Miss Y’s case was decided, the government had yet to publish guidelines on the operation of the Act. These have since been published, but offer very little by way of supplementary instruction to doctors. So, as Savita Halappanavar’s case illustrated, there is still a great deal of ambiguity around the point at which a woman’s life will be found to be at sufficiently serious risk to justify an abortion. This problem may have recurred in a different guise in the Miss Y case. The leaked draft HSE report suggests (rightly or wrongly) that although some of the service providers who met with Miss Y earlier in her pregnancy noted her severe distress, none appreciated that she was ‘actively suicidal’ until much later. The guidelines to the Act use the phrase ‘suicidal intent’ to describe the condition of a woman entitled to an abortion – suggesting, perhaps, that the woman must be able to evidence a determination to kill herself before she can receive abortion care.

Third, the Act, following the X case, says that a woman may not access an abortion unless it is the ‘only’ means to save her life. The Act, and its accompanying guidelines, also emphasise that the doctor must preserve unborn life insofar as it is practicable to do so. Where a pregnancy is in its second trimester or later, these two provisions are likely to combine to create a ‘viability’ barrier to abortion access. The published guidelines specifically anticipate that a woman whose pregnancy is viable is likely to be required to submit to early delivery by induction or C-section, as appears to have occurred in Miss Y’s case. No Irish court has considered a case about the termination of a viable pregnancy, and so the legal basis for these instructions is doubtful. In addition, we do not know whether the Act might be read to require that a woman’s pregnancy be prolonged for a number of weeks, until it reaches viability.

Finally, it seems clear that the Act’s intense focus on the preservation of unborn life, and on the facilitation of live birth where possible, means that women’s other healthcare needs are likely to be compromised. In particular, doctors are left with little guidance on how they should proceed where a woman will not consent, for instance, to a proposed early delivery. In Miss Y’s case, we know that High Court orders were sought to facilitate her hydration, and the C-section, because she had refused to co-operate with the course of treatment. There is a right of appeal – to a further panel of doctors – from a refusal of certification under the Act, but Miss Y did not use it, and there are questions about how accessible it is to a woman who is likely to be seriously ill or distressed. Ultimately the orders obtained in the High Court were not used. The circumstances by which she finally gave her consent are not known. The HSE inquiry will not tell us anything about the legal arguments advanced in the High Court on behalf of the state. There is a reporting embargo on the case itself, and we have scant reported case law on compelling medical care for non-compliant pregnant women. At a time when Irish maternity services are under intense scrutiny, following the deaths of Savita Halappanavar, Dhara Kivlehan, Bimbo Onanuga, Jennifer Crean and Tania McCabe, Miss Y’s case underscores how little space there is for women’s autonomy in a system geared to the protection of life, even at the cost of health.

Where to now?

It is clear from Miss Y’s case that the possibility of obtaining an abortion in Ireland remains very limited. Women who can travel will continue to do so. Women who find themselves needing an abortion in later pregnancy are likely to be wary of the possibility that they will be compelled to give birth as Miss Y was. Meanwhile, a strong coalition of groups is campaigning for the repeal of the 8th Amendment, which since 1983 and via the X case, has come to govern every case of maternal-foetal conflict. The current government argues that there is no appetite for a referendum. It has also indicated that it will not be moving to amend the new Act at least until its operation comes up for review in June.

That said, newspaper opinion polls and large crowds at pro-choice events indicate that a growing majority of Irish people accept that the abortion law must be liberalised to some degree. Repealing the 8th Amendment would open the discursive space in which to do so. Whatever alternative interpretations of the Amendment are possible in theory, they have not been translated into practice. We may one day see a constitutional challenge to the new Act, but this is unlikely and unpredictable given the burdens which costs, delay and procedure impose on pregnant or ill litigants. Repeal is the best route to constitutional change. The recent constitutional amendment on children’s rights and the forthcoming referendum on marriage equality both indicate a constitutional norm of using referenda to correct moribund interpretations of the constitution.

Once repeal is achieved, our attention must turn to the question of new abortion legislation. Opinion polls suggest strong public support for access to abortion on the grounds of rape, incest, fatal foetal abnormality and serious risk to physical health.If the current Act is anything to go by, the procedures put in place to regulate such conservative new grounds are likely to be a deterrent to access. Feminist groups, meanwhile, hope for something much broader, including removal of the 14 year penalty for the office of ‘destruction of unborn life’ and the possibility of ‘free, safe and legal’ access to abortion without restrictive grounds. (The Abortion Rights Campaign, Women Helping Women, RealProductive Health, ROSA, and Doctors for Choice are the ones to watch). Feminist campaigning around abortion rights must aim at human rights oriented legislation which allows for the broadest possible period of legal access to medical abortion on request, followed by the broadest possible grounds for access thereafter. Some feminists would prefer that we not legislate for abortion at all, but rather allow doctors and women to work out their own position in the space left by decriminalisation and repeal. However, given the conservatism of the medical profession in relation to abortion access, and bearing in mind the disproportionate power of anti-abortion groups to intimidate women, legislation will be required to empower and protect pregnant women and abortion care providers and to clarify their rights.

‘Spare a Thought for This Shared History’

Marian Larragy’s (for the LIFN) Letter to the Editor, published in the Irish World, 03/05/14:

Of course the shared history of Ireland and Britain on abortion should be remembered, but the lessons to draw are not necessarily those suggested by Ann Campbell in her letter of 26th April, ‘Spare a thought for this shared history’.

The 1967 Act in Britain (it does not apply in Northern Ireland) did not gently change the number of pregnancies terminated by women. What it did do was to recognise the reality of the choices that women were sometimes faced with. The reality is that 12 women a day, or perhaps 150,000 women in total since 1967, have needed to travel to England to seek the care they need. This is a political failure to face up to reality, in Ireland south and north. We have the technical means both to help prevent unwanted pregnancies and to terminate unwanted pregnancies at a very early stage and it is more than time that both Irish states facilitated proper use of these medical advances in ways that respect the dignity of women and a woman’s right to protect her health and her life by exercising responsible judgement.

Marian Larragy

London Irish Feminist Network

London NW1

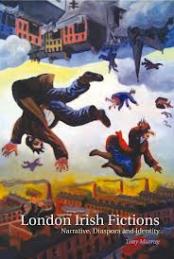

Book Review: ‘London Irish Fictions’ (Tony Murray)

London Irish Fictions: Narrative, Diaspora and Identity

by Tony Murray (Liverpool University Press) £19.76 http://tinyurl.com/jw8rw39

This is a book about Migration in which the author explores memoir and autobiography to demonstrate his thesis that the telling of stories creates its own form of “narrative diasporic space” and the reconfiguring of identity. The book is divided into three sections: The Mail-Boat Generation, The Ryanair Generation and The Second Generation.

In ‘Escape and its Discontent’, Murray offers an insightful interpretation of Edna O’Brien’s discourse on mother and nationhood which underpins many of her characterisations and allows us to appreciate the loss of identity that can occur through the conflation of escape and exile. This theme is developed further in ‘Departures and Returns’ where the novels of John McGahern are examined. Murray shows how McGahern illuminates migration in psychological ways as well as socio-economic ones. He discusses the emotional dynamics of the diaspora as played out in letters, family dramas and hauntings.

The chapter on ‘Ersatz Exiles’ highlights inter-ethnic discourses referencing Bronwen Walter’s work and skilfully uses texts to illustrate issues of self-parody, Irishry and deliberate mythologization. The chapter entitled ‘Gendered Entanglements’ explores the fiction of Margaret Mulvihill with regard to contested alliances around ethnicity, gender, class and religion. In particular how the author is emotionally bound to the cultural narratives of her past and her lack of self-confidence in her national identity within the 1980s anti-Irish prejudice common in London. Her novel ‘Low Overheads’ examines the volatile social implications of an unwanted pregnancy, especially fraught in Ireland at this time. Another feature to this novel is the backdrop of the conflict in Northern Ireland and the interaction with English people with little or no knowledge of the shared history.

There is a marked shift in the fiction examined in ‘Ex-Pat Pastiche’ best summed-up by a heightening perception following abuses of the Terrorist Act, the Hunger Strikes and the increased political awareness of the London Irish – as portrayed through Joseph O’Connor and Robert McLiam Wilson’s characters with their postcolonial and intra-ethnic references and attempts to find a multi-dimensional identity in keeping with their generations instincts and sensibilities.

In ‘Transit and Transgression’, Murray refers to Mary Robinson’s inaugural speech which he suggests contributed to the emergence of increasing numbers of Irish female writers. Through the writings of Emma Donoghue and Sara Berkley, he highlights a sense of “provisionalism” in which identity is constantly shifting and challenged. In ‘Going Back’, Donoghue explores how exile occurs both internally and externally through a “queered sense of self” alongside a fundamental sense of alienation from her nationality and mono-cultural categorisations. Sara Berkley’s ‘The Swimmer’ tells of the irreversible psychological journey that has been taken to escape emotional damage but by becoming a migrant she is held in a form of suspension, ambivalence and uncertainty. Both women are caught in a “diasporic limbo”.

Part III of the book examines how second generation Irish children negotiated and incorporated, or not, their dual-cultural backgrounds where language, accent and religion are central and memory and imagination become porous.

This is a scholarly book with many sensitive insights and reflections.

Sarah Strong

Lest we forget: Three Anniversaries

2014 is the 30th anniversary of two tragic events: the death in childbirth of 15-year-old Anne Lovett, and the infamous Kerry Babies Case. Both occurred in the shadow of the Eighth Amendment of the Irish Constitution which passed into law in January 1983 and placed the life of the unborn, from the moment of conception, on a par with the life of the mother.

Eileen Flynn

A third event – the decision by an unfair dismissals tribunal in February 1984, that the sacking of school teacher Eileen Flynn by Catholic secondary School in New Ross, Co. Wexford was not unfair – raised troubling questions about the condition of women in Irish society. Eileen had been sacked because she was pregnant, unmarried, and living with a separated man and higher courts upheld the sacking the following year. See http://www.bailii.org/ie/cases/IEHC/1985/1.html

Anne Lovatt

On 31st January 1984, on a moss-covered stone at the feet of a statue of the Virgin Mary outside Granard, Co. Longford in the Republic of Ireland, Anne Lovett lay dying alone beside her dead baby. Anne was moved to hospital, but did not survive. In a small town like Granard, although they initially claimed otherwise, it seems that everyone knew that Anne was pregnant: her family, her classmates, the teachers in the Convent of Mercy School, as well as the town folk. Nobody chose to intervene, not even the Gardai who should, by rights, have searched for the man or boy responsible for having sexual intercourse with an under-age schoolgirl. Nobody chose to intervene, it would seem, because to do so would interfere in family matters. After all, it is the family, not the individual, which is the basic unit of society enshrined in the Constitution of the Irish Republic.

The Kerry Babies

Thirty years ago in April, 1984, Joanne Hayes gave birth at the family farm in Abbeydorney, Co. Kerry, again in the Republic. The child did not survive. Joanne was unmarried and this was her third pregnancy. She was in a relationship with a married man who, being something of a stud, became known locally as ‘Shergar’ after the famous racehorse turned stud kidnapped in 1981 by masked men, said by some to be members of the IRA in pursuit of ransom. Joanne, of course, was not lauded for her fecundity but labelled ‘murdereress’ and ‘slut’ and a lot worse. She was charged with murder (later dropped) and forced to endure an 82-day all-male staffed Tribunal set up by the Irish state in the town of Tralee which took on the aura of the infamous witch trials in Salem, Alabama in 1692/3. If that wasn’t enough, Joanne was also charged with killing another baby with stab wounds to the heart which washed up on the beach near Caherciveen, Co. Kerry. Forensic evidence later found that Joanne was not the mother of the Caherciveen baby. [Irish Times Journalist, Nell McCafferty wrote ‘A Woman to Blame: The Kerry Babies Case’ [ISBN 13: 978-1855942134], £9.50 PB. Kindle £5.56.

This is us!

Who are we?

We are self-defining feminist women in London who also identify as having some connection with Ireland. Among our members are women who are former residents of Ireland, women with Irish heritage and ancestry and Irish citizens.

Why are we?

During an impromptu meeting of women at a picket of the Irish embassy after the death of Savita Halappanavar in 2012, we agreed that there were few established forums for Irish women’s voices or perspectives in London – in particular, for feminist voices. We also noted that this situation was exacerbated by the closure of the London Irish Women’s Centre in 2012. So the London Irish Women’s Network (LIWN) was set up with two main aims:

1) Support each other in exploring and taking action on issues affecting us in Ireland, London and the UK.

2) Work together to make sure our voices are heard on the diverse range of issues that matter to us.

What we have been doing so far:

– Producing a newsletter detailing events and issues of relevance to Irish feminists.

– Promoting the film “Breaking Ground, the story of the London Irish Women’s Centre”

– Facilitating consciousness-raising groups

– Collaborating with other groups on projects of mutual interest:

- pro-choice activism with IMELDA (Ireland Making England the Legal Destination for Abortion) and My Belly Is Mine (in solidarity with Spanish women)

- Irish History Month organized by CRAIC (Campaign for the Rights and Actions for Irish Communities)

- Women’s Studies Without Walls

- Votes for Irish Citizens Abroad (VICA)

What will we do?

As a non-hierarchical grouping, we aim to support and provide a forum for any self- identifying women with a connection to Ireland who would like to explore and take action on issues that matter to them. These issues can be similar or different to those already pursued by some of our members.

Get in contact to get involved:

https://twitter.com/LIrishFemNetw @LIrishFemNetw

lifn32@virginmedia.com – email to be put on our newsletter mailing list!

https://www.facebook.com/groups/londonirishfeministnetwork/